|

Today I justified the “movie

producer” title on my business card. The movie

is the Iliad. The production has a cast

of 1200 extras. The crew from Munich– Cameraman

Werner Kurz, Special effects supervisor Karl Baumgartner

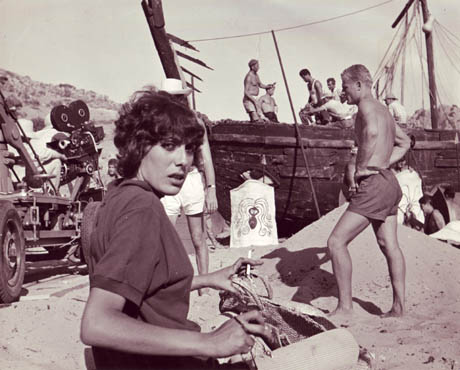

and Script girl Pia Arnold– actually began shooting

the film two days ago at Tolon, a beach about 120 miles

from Athens. I left my collaborator Susan Brockman in

charge in Tolon and I am back in Athens to look at the

rushes.

The shooting script, by Mario

Puzo, the civilian administrator of the 442nd Army

Reserve unit in New York, opens with a huge battle around

the Greeks’ beached ships.

For that spectacular scene, Susan and I had meticulously

assembled the ships, shields, costumes and other requisites.

The Greek government had been most cooperative. For

ships, the port of Piraeus had contributed 6 water-logged

hulls long sunk in a caique graveyard outside the harbor.

Then shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos contributed a

floating crane to raise and load them on to a LST landing

craft--the L188-- supplied by the Greek Navy. The L188

then ferried them to the location. ( Unfortunately the

LST broke its propeller unloading the cargo in shallow

water.)

The local authorities then supplied a work gang of prisoners

to reconstruct the ships. For masts, I had the cooperative

prisoners borrow telephone poles from the surrounding

area ( temporarily interrupting local telephone service.)

And the Greek Army, at the request of the Ministry of

the Interior, supplied 1,200 extras, who were outfitted

in loincloths and sandals by student interns attracted

by the illusionary rumor that Marlon Brando would be

arriving.

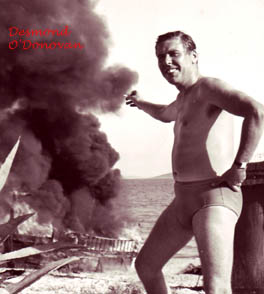

Despite all these efforts, the new director, Desmond

O’Donovan, claimed that it was too cloudy to shoot

battle scenes. Instead, he wrote a"weather contingency"

scene in which a dog snatches a piece of meat from a

pot at a campfire. He said it would provide a “cinematic

metaphor” to depict the hard times the Greeks

were suffering in their siege of Troy.

Now, in the aptly-named

Apollo screening room in Athens, I watch the results

of this contingency with horror. There are 37 retakes

of the mangy dog . Meanwhile, I am billed daily for

the cases of orangeade and mounds of sis kebab the 1,200

hungry extras consume while they wait for the sun, draining

a significant portion of my $36,000 production budget.

Watching the rushes with

me are three visitors from Hollywood: Polish-born Rudy

Mate, Russian-born George St. George, and Italian

born Maria. Rudy had been a legendary cinematographer--

photographing Dryer's classic The Passion Of Joan

of Arc-- before becoming a Hollywood hack director.

He is now in Athens to scout locations for his next

film, The Lion of Sparta. St. George, who had

escaped the Russian revolution via Shanghai and wound

up in Hollywood, is his producer and sidekick. Maria,

a barely-legal actress, is Rudy's lover. I had met them

earlier in the day in the lobby of the Grand Bretagne

hotel and invited them to the screening.

“Interesting ,” Rudy Mate says, after the

dog’s 20th lunge at the bone. (I later learn from

Maria that “Interesting” is Mate codeword

for “awful”). “I’m not sure

I am familiar with this director O’Donovan..”

“It is his first film,” I reply.

I add that the script

is also by a first-time writer, Mario Puzo.

St. George, intrigued by the

cooperation I am getting from the Greek government,

asks "How did you get the Greek Army?"

More to the point, Maria asks,

“How did you get in this mess?”

Over dessert in the Cafe Floca, I explained how what

had began as a love story had turned into an organized

flight from reality (with me as tour leader).

The adventure traced back to my temporarily suspension

from Cornell. As my penance, I read Richmond Lattimore's

translation of the Iliad. This effort might have ended

in no more than the usual cerebral exercise if not for

two coincidences. First, Susan Brockman, a Cornell coed

I fancied, on seeing my conspicuously-toted Iliad, said

that it was her life’s ambition--at least that

week-- to play Helen of Troy in a movie. Second, I read

a New York Times story that Zervos Pictures in Athens

and Mosfilms in Moscow had tentatively agreed to make

a Russian-Greek coproduction of the Iliad.

Seizing the opportunity, I

dashed off a telegram to Zervos Pictures: “IF

YOU ARE NOT IRREVOCABLY COMMITTED TO THE RUSSIANS, WOULD

YOU CONSIDER DOING INSTEAD AN AMERICAN COPRODUCTION

WITH MARLON BRANDO AS ACHILLES, JAMES MASON AS AGAMMEMNON,

RICHARD BOONE AS ODYSSEUS AND SUSAN BROCKMAN AS HELEN

OF TROY.”

I could not send it immediately because I was concerned

about my return address. I was living at my parents’

home in Rockville Center and feared that asking Zervos

to reply to Ed Epstein, c/o Betty&Lou Epstein might

cast my credibility as a producer in question. Susan’s

sorority house at Cornell, Alpha Epsilon Phi, had a

similar problem, but Susan found the solution: her father.

David Brockman, was a successful financier,

with a large office, and impressive cable address: GILESACT

NEW YORK, which I used as my return address.

About a week later David Brockman

received a telegram from George Zervos, the President

of Zervos Pictures . “I AM WILLING TO PUT UP 7

MILLION DOLLARS FOR BELOW-THE-LINE PRODUCTION STOP PREFER

TO DO THE ILIAD WITH EPSTEIN’S COMPANY INSTEAD

OF THE RUSSIANS.” As David Brockman had not seen

my original telegram offering to provide Marlon Brando,

he was impressed that someone would offer a friend of

his daughter $7 million. He asked Susan to arrange for

me to meet him and Arnold Krakower, a successful NY

divorce lawyer. The meeting then expanded to include

another of Brockman's associates, Ben Javits. Ben was

the brother, eminence grise and law partner (Javits

& Javits) of New York Senator Jacob Javits.

It turned out he reveled in influencing world events,

or at least Grecian ones. He especially liked

the idea of blocking a Russian coproduction and offered

to have his brother write letters to everyone who mattered

in Greece.

Even though I had not

previously conceived of my adventure as part of the

Cold War, I accepted his offer. Why not block the Russians?

At Krakower's suggestion, we formed a partnership–

Iliad Productions, Inc– in which he and Brockman

and Krakower would provide the initial money for preproduction.

“You have to go to Athens right away,” Javits

said, adding urgency.

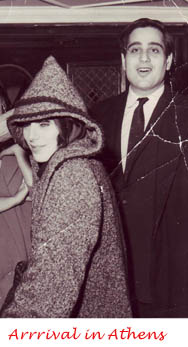

A few days later, September

15,1959, Susan and I made our initial trip to Greece.

Her father, who owned among many industrial companies

a travel agency, provided us with first class tickets

to Athens on a KLM “sleeper” flight. As

he had promised, Javits had opened all the doors for

us. Over the next week we met government ministers,

shipping magnates, and others in the Athens power elite

that responded to Javits' letter. And we had a

great time being wined and dined in tavernas.

The first deal I made was with Spyros

D. Skouras, the namesake nephew of Spyros Skouras, the

Chairman of 20th Century Fox. Skouras owned a

local film studio in Athens (Skouras Films) as well

as the lucrative Eastman Kodak film franchise for all

of Greece. After he listened to my plan

for the Iliad, he asked who would play Achilles.

When he heard Brando’s name, he became so excited

that he wanted to sign a contract that day. “Forget

Zervos, forget the Russians, I will be your partner

– but you must get Brando.” I told him Brando

had not yet agreed. “He will,” Skouras said.

Two days later, Skouras and I signed a “memorandum

of understanding” in which I would supply Brando,

the script and the director, and Skouras would pay for

the production in Greece.

Next, Minister of Industry

Nicholas Martis, moved by Javits’s letter, offered

a battalion of soldiers from the Greek army, horses

from the King’s guards, and whatever else I needed

for the Iliad. He then said he would also like to host

a small dinner at his home for Brando. “When will

Marlon arrive?” I explained Brando would need

to approve the script.

“Just give him Homer’s Iliad to read,”

Minister Martis suggested. He wrote a letter stating

“I will do everything in my power to ensure that

every reasonable facility is provided by the authorities.”

With this impressive-looking letter

from Minister Martis and the agreement with Skouras

Films, Susan and I triumphantly returned to New York.

A telegram was waiting from Skouras: “DEAR ED,

IT HAS BECOME AN OBSESSION WITH ME. WE MUST GET BRANDO

FOR OUR PICTURE..SPYROS.”

By this time, Arnold

Krakower had taken a direct hand in the search for the

director. As a top divorce lawyer, he had dealt with

the director Sidney Lumet,

whose divorce from Gloria Vanderbilt he was handling.

To accommodate Krakower, Lumet invited me for breakfast

at his penthouse at 10 Gracie Square, which overlooked

the Mayor’s mansion. Lumet, though only

36, was no amateur. The son of an actor and dancer,

he had made his stage debut at the age of 4 in 1928

at the Yiddish Art Theater. He had been nominated for

an academy award for directing 12 Angry Men.

After selecting my breakfast from a plate of smoked

salmon, I asked him about Brando, whom he had just directed

wearing a snakeskin jacket in The Fugitive Kind.

He said Brando would

be perfect, and he would be “keenly interested”

in directing it once Brando signed on. He then asked,

“Do you have a script?”

“I’m still working on it.” Actually,

all I had was a 30 page treatment written on spec by

a very talented playwright, Sloane Elliott. Sloane,

who was also a classicist, was an aficionado of Homer--

and had travelled to almost all the Greek islands.

He was not, however, interested in writing a shooting

script.

A script was not my only problem. “Once

you have a script, you will need to put $500,000 in

an escrow account before Brando’s agent, Audrey

Woods, will allow him to read a page of it.”

I had neither a script nor

$500,000. Having made these cold facts of the

conventional movie business clear to me, Lumet politely

ended the breakfast, and walked me to the elevator.

While awaiting it, I told him that the Greek government

was providing its Army for the battle scenes, and that

Spyros Skouras was willing to finance the shooting of

those scenes.

“I guess you could shoot the battle scenes with

a second-unit,” he said, as the elevator doors

opened.

“With Achilles wearing a mask?” I asked.

“So Brando could still be used by the first unit?”

“Lets see how they turn out, bye .”

As my vertical chariot whisked

me down from the penthouse, I grasped a new strategy:

To first shoot the battle scenes in Greece with a second

unit and then get Lumet to direct Brando in a studio

in America. But I still would need a script.

A second problem was

the American draft. Being suspended from Cornell, I

could be drafted at any moment by the U.S. Army and

that might provide unwanted experience in non-Homeric

battle scenes. The alternative to the draft was joining

a reserve unit but, given the number of men with the

same idea, all the reserve units had long waiting lists.

As it happened, my cousin had a means to jump the cue.

He steered me to a very influencable civilian administrator

at the 442nd Bagel-baking reserve, Mario Puzo. Puzo,

though only 39, looked like an overweight wreck. When

he told me he was a writer– even if for magazines

with names like Stag– I told him I needed a screen

writer for the Iliad. A deal was instantly struck to

kill two birds with a single stone : Mario would slip

me in a reserve unit in such a way that it would not

interfere with my activities as a movie producer; I

would pay Mario $400 for a 40 page shooting script for

the battle scenes. After I brought Puzo to meet Krakower,

he said “I’ll give him the $400 and a contract,

but no one will ever believe this guy is a writer.”

Puzo did deliver, however, the promised script.

Krakower showed no enthusiasm

for a bifurcated movie. “You need a single director,”

he said authoritatively and found a candidate: Lewis

Milestone.

Milestone was an old timer par excellence. In 1927,

he had won the first (and only) academy award given

for Best Comedy Director. When Krakower had recently

met Milestone at a Hollywood dinner, Milestone had complained

that because of age discrimination he could not get

a picture to direct. So Krakower proposed the Iliad

and Milestone showed “real interest in getting

back in the game,” as Krakower put it. After our

initial meeting, where I gave him Puzo’s script,

we then carried on a month long correspondence about

Homer. It ended abruptly when he found out I could not

pay his fee– or any fee– in advance.

Returning to the idea of splitting

the movie, I found Gregg Tallas. Born Grigoris Thalassinos

in Athens, Tallas was down on his luck in America–and

broke– and wanted to go back to Greece. His directorial

experience had been limited to two films Prehistoric

Women and Sirens of Atlantis he did ten years ago, both

of which failed at the box office. Although Tallas claimed

to have directed the Second Unit on Gone With The Wind,

he received no credit for it.

Despite his lack of credentials,

he had one real advantage: he was willing to defer his

compensation until the film was finished. All he asked

for was a first class ticket to Athens. Since I could

get the first class ticket gratis from Brockman’s

travel agency, and desperately needed a director, I

hired him for the 2nd Unit (hoping, without any real

basis, Lumet might later take over the First unit.)

On July 15th, I

returned to Greece with Susan and Tallas-- and $50,000

raised from Brockman, Krakower, Sloane Elliott and my

father. We moved into the King George Hotel, where the

owner, George Calcannis, anticipating the arrival of

Marlon Brando, had given us the bridal suite.

Finding the right location

for the Iliad proved much more time consuming than I

had anticipated. In late July, the Greek Navy provided

us with a spare gunboat, the BB36, to scout locations

on various Greek islands. We saw almost as many islands

as Odysseus– Skiros, Andros, Hydra, Patmos, Lesbos,

and Thera– with beautiful beaches, but none had

the requisite electricity, hotels, or airport connection.

Fortunately, by the time we returned from our futile

search, Minister Martis had found the ideal location:

a not-yet-occupied hotel on a deserted beach at Tolon

that the Ministry of Tourist would provide free. He

added “Brando will be the first guest.”

Meanwhile, director Tallas

had become a problem. He also refused to work from Puzo’s

shooting script, saying it was “unprofessional.”

More damaging, he added to Skouras’ angst by telling

him “Hell will freeze over before Brando comes

to Greece.” But matters really came to a head

when he told Colonel Cactemilitus, our liaison with

the Greek Army, that the call sheets I had given him

specifying how many extras were needed each day were

“Plucked out of thin air.” In the midst

of his subversive conversation with the Colonel en route

to Tolon, I maneuvered him out of the car, took him

a small café in the middle of nowhere, fired

him, and then proceeded with the Colonel to inspect

the location.

At this point, with shooting

scheduled to commence in two weeks, I had to fill the

directorial gap. So I cabled the London talent agency

that was supplying me with 3 stunt men in September.

Could it also supply a Second Unit Director? Enter on

September 7th Desmond O’Donovan, an ebullient

Irishman with a great gift of gab. He told me he had

produced a British TV show about a dog called, Whirligig,

when he was just a teenager and, more recently, worked

(uncredited) with his half-brother Kevin McClory on

80 Days Around the World . With just five days

to go before shooting, I was in no position to challenge

even these scant credentials. So I sent him, along with

the 3 stuntmen– Joe Powell, Pat Crane and Frank

Haydon– directly from the airport in Athens by

taxi to the free Hotel in Tolon.

"That's how we got the dog scene,”

I concluded.

"Fascinating," Mate

said, as he and his associates rose in unison to leave

the Floca. "By the way, I wouldn't want to contradict

your director, but the best battle scenes I've shot

were in cloudy weather."

|