|

"Why

do we study coup d'etats in a course on politics?" asked

Jacob Foxx, Assistant Professor of Government at Harvard.

Foxx slowly surveyed

the packed lecture hall, letting the students stew for

a moment in their own silence. The five-hundred-odd

seats in Lowell Lecture Hall were full. A few students

were even squatting Indian-style in the aisles. Without

question, his course, "The Pathology of Politics," was

now the most popular in the Government Department. Not

the great Galbraith in the Economics Department nor

the celebrated Schlesinger in the History Department

had as many students in their lectures.

"No takers?" Foxx asked,

breaking the silence. His wiry brown hair, which flopped

over his brow like a schoolboy's, made him look more

relaxed than he was "Then let me answer my own question."

After pausing a moment, he began. "The coup in its purest

form is an act of' statecraft. Its objective is not

overthrowing the mythic political system nor paper constitutions,

but the instruments of power that control the state.

Perhaps it is not in your standard textbooks, but the

coup cuts to the heart of the study of politics."

Like an orchestra conductor,

Foxx punctuated each point he made with both hands slicing

the air. Finishing this brief introduction, he stepped

back from the lectern. He tended to slouch slightly

when he relaxed. Being nearly six feet four inches tall,

he was somewhat self-conscious about his height. The

undergraduates seemed quite impressed with his lecture.

This was only his third year at Harvard, and already

his course had received a rave review in the "Confidential

Guide to Classes" published by the Harvard Crimson.

It described Government 233a as "the hottest thing going

on in an otherwise dead Government Department." And

it was especially kind to him, noting that "Professor

Foxx avoids the usual humdrum about legalities, constitutions,

etc. Instead, he applies his own Machiavellian cunning

to political power." It concluded its recommendation

with "New, original, and requires very little outside

reading." Actually, the review had proved something

of an embarrassment. His colleagues in the Government

Department were teaching courses about the very sort

of constitutions and formalities his course derided.

The review added fuel to an already burning fire. Foxx

knew from remarks made at faculty meetings that his

colleagues considered his presentation overly dramatic

and overly conspiratorial. On the other hand, he was

undeniably drawing more students than any other lecturer.

They would have to take that fact into account when

he came up for tenure in the spring.

While the class watched,

Foxx quickly drew a maze of circles, squares, arrows,

and interconnecting lines on the backboard behind him.

"Think for a moment of government as a labyrinth," he

resumed. "Painted on the outside Walls of this labyrinth

are figureheads— a president, Congress, Cabinet members.

To find the power, it is necessary to enter into the

maze itself. Here, in nameless bureaus are faceless

men that keep records, reports, and dossiers." He paused

to allow the students to catch up with him in their

note taking.

A hand shot up in the

front row. Foxx instantly recognized it as belonging

to Brixton Steer. Even down to the bow tic, young Brixton

looked like an exact replica of his elegant father,

Ambassador Steer. Since Brixton was also his tutee,

Foxx knew how conscientious he could be. "Question,

Mr. Steer?"

"If I understand you

correctly, Professor," Steer began over-deferentially,

"you suggested that elected officials are merely fronts

for hidden power elites."

"You got it. The modern

bureaucratic state," Foxx replied.

"Then I don't quite

understand why coup d'etats often aim at overthrowing

these figureheads?" Steer sat down, knowing his question

would be answered.

Foxx said, nodding

as if he were taking in its fullest implications. He

welcomed questions because they broke the tedium of

the lecture, and allowed him to refocus the students'

attention. "I did not mean to minimize the important

function of elected leaders. Even though they do not

exercise real power in this model, they still symbolize

it in the public's imagination. The first objective

of the coup d'etat is to capture the real nerve centers

of government. This may be a military communications

center, a counterintelligence agency, the censorship

authority, or whatever. Once the coup controls the inner

machinery that collects and disburses information, it

controls the government. If the coup-makers want to

publicly identify this change in power, this requires

some sort of symbolic coup d'etat-which is what we read

about in the newspapers. It involves overthrowing and

possibly arresting the elected leaders. Such a symbolic

coup should not be confused with the real coup which

preceded it."

Foxx could see that

he was losing the interest of the class. The signs were

unmistakable: papers could be heard rustling, eyes began

wandering around the amphitheater, and shoes scraped

together. He could almost feel the students becoming

fidgety. He had been too analytical in describing the

coup d'etat, he thought. What students at Harvard demanded

was not disembodied concepts but interesting anecdotes—

anecdotes they could repeat in their houses and clubs--

they could use later to impress their friends.

"Consider, for example,

what really happened in Venezuela in 1948." As he began

his anecdote, he could see students perking up their

cars. It reminded him of police dogs responding to a

subsonic whistle. "I happened to be in Caracas that

year doing research on my thesis. The real coup occurred

in October, when the counter elite seized control of

such power centers as the liaison with the U.S. Military

Mission in Caracas, which then operated all the military

airports in Venezuela; the Central Telephone Exchange,

which controlled communications between the capital

and the provinces; the anti-subversive unit of the National

Gendarmerie, which held dossiers on key politicians;

and the State Security Agency in the Ministry of Interior,

which could neutralize any pro-government military unit

by issuing fake marching orders. After they had gained

real power, the coup-makers in turn waited until November

fifteenth, 1948, before overthrowing the President and

closing down Parliament."

He hesitated for a

brief moment, seeing his tutee, Arabella, out of the

corner of his eye. She was entering the lecture on mock

tiptoes.

When she reached the

third row, a young man in a charcoal suit and white

buck shoes offered her his seat. She had that effect

on men. She sat in his stead, easing one leg over the

other, she dangled her calf so that her toe just touched

the floor.

Foxx touched his hand

to the back of his neck. It was damp, the first sign

of anxiety. "The coup may thus provide us with the only

glimpse we will ever get of the actual power structure."

Arabella couldn’t help

but smile at her tutor’s performance. He reminded her

of a man on a tightrope, who smiled to impress the audience

with his utter confidence while betraying his fear with

short tentative steps. At times, she held her breath,

sure that he would fall flat on his face with some point

he was making, but he always managed, somehow, to regain

his balance. At Oxford, where Arabella had studied Philosophy,

three years, she had never seen a professor quite like

him. She thought that he was pushing his "hidden power

structures" much further than logic allowed, but his

enthusiasm to clear away the underbrush made her head

spin, like when she had drunk too much champagne.

His lecture concluded,

as it always did, just as the chimes began ringing.

He was nothing if not punctual. He always tried to avoid

watching the students as they filed out. Experience

had taught him that even the briefest eye contact might

cause students to linger and ask half-articulated questions

about the nature of politics. He knew by the time the

last chime struck the lecture hall would empty out.

Like everyone else, students were creatures of habit.

Turning to the blackboard, he began erasing the maze

of symbols.

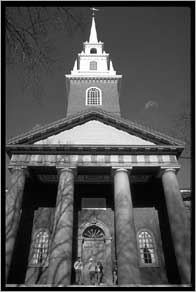

Foxx whistled a tune

he couldn't quite remember as he walked across the Yard.

It was only November, but the frost had already defoliated

most of the trees on in Harvard yard. He tried to protect

himself against the cold wind by hunching his shoulders,

though he knew it was a illogical gesture.

His office was on the

third floor of Littauer Center. It wasn't very large,

but he had taken pride in furnishing it with the few

possessions he care about. His ex-wife Lulu, a luscious

Parisian photographer, had bought the Spanish colonial

desk in Venezuela. It was all he had to show for his

four years of service there or, for that matter, his

four years of marriage. Lulu turned out to be a lulu:

She went to France to visit her parents and never returned.

Eight months later, he received a note from her saying,

"Sorry but I don't breed well in captivity. Divorce

papers on route."

The leather Chesterfield

sofa he had bought soon after receiving Lulu's letter.

He got it at Turtle’s auction house in downtown Boston.

Its previous owner, a professor of Art history, was

famous for seducing his tutees on it. Its seventy-six

inches of black pleated leather turned out to be a perfect

length for him to snooze on. Over it was his latest

acquisition, a Belle Epoch etching by Beardsley.

The shelves were conspicuously

empty of books. As far as he was concerned, few books

had been written on politics that deserved to be reread.

On the floor was an Armenian dragon carpet. It had been

a gift from his mother. She never said where she had

gotten this museum piece— or very much else, except

on a “need to know” basis. She had refused even to tell

him even his father's proper name. All he had ever learned

of him was that he was some sort of international businessman.

Most of Foxx's youth was spent traveling through Europe

with his mother. She usually identified him as a nephew

or cousin. He played along with this deception, arranging

his identity and cover story to fit hers. Only after

die died in a car crash did he begin to establish his

own identity, first as a political scientist at UCLA,

then as a propagandist in Venezuela, Now, at thirty-three,

he was an Assistant professor at Harvard.

Sitting at his desk,

he leafed through the report on his desk called “'Praetorian

Politics." He would be presenting it at the colloquium

he had been invited to in New York that Friday.

His eye than fell on

a post card. It was the latest move in the correspondence

chess game he had been playing for two years with an

opponent whom he had never met. He slid out the chess

set from his desk drawer. It was more interesting than

his presentation. Was his opponent attempting to lure

him into a trap? He scribbled a counter move on a postcard.

A knock on the door

interrupted him. Through the translucent glass, he could

see a student's silhouette. "One moment, please," he

called. He put the chessboard back in the drawer— he

want his students to think of him as a compulsive game

player— and returned the report to his desk.

"Sorry to break in

on you like this," Arabella said, standing in the open

doorway. "I was hoping that we could re-schedule my

tutorial."

"Isn't it scheduled

for later this afternoon?" "Yes, 4 pm. But my sister

Tina left a message she is going to call me at home

then. Can't be in two places at one time, though I sometimes

wish I could. She is coming to Cambridge. Perhaps I

can bring her to your lecture, Professor Foxx."

"why not. Is she interested

in politics: "Pathological politics," she corrected.

"No, not really. Tina's interests lie..." She was quite

content to let her sentences dangle in midair. Men usually

rushed in to complete them favorably for her.

"Elsewhere," Foxx completed

the sentence on cue. "When would you like to do the

tutorial?" Is this a convenient time."

He picked up the report

on his desk as to show how busy he was “I have to edit

this paper..."

She had that confidant

glint in her eye saying, as if to say she knew something

he didn’t know. He wanted to tell her to come back the

following the week, just to teach her a lesson about

who was in control. Instead, he heard himself say, “"But

I can do that later paper later. Sit down, please”

Leaving the door slightly

ajar, she made her way to the Chesterfield. The sun,

streaming in the window behind her, revealed the outlines

of her lithe body through a loose gauze dress. She slid

into the sofa, tucking her legs under her skirt, with

great agility.

He again felt those

tell-tale beads of perspiration forming on his neck.

He hoped she did not see them. He had known Arabella

only since September, when she had transferred from

Oxford to Harvard. He had been impressed first with

her mind. Although she was only nineteen, she applied

the rigor of a trained logician to everything said in

her presence. She relished challenging whatever points

he made. A belle dame sans merci. But it was her body

that came to unnerved him. "Have you had a chance to

read the chapter on the labyrinth, Arabella?"

“Every word, twice.”

She poised her head, sphinx like, on a bridge she made

for it by clasping her hands together.

"Do you agree that

possessing a blueprint to the labyrinth of government

is in itself tantamount to power?"

"The terms of your

argument are clear enough. The power to control a government

resides in the agencies that control intra government

communications. If a potential usurper can identify

and locate these agencies, his chances of success are

increased."

"That's an excellent

summary of the thesis." He liked the terse way she stated

things, like precise hammer blows on a nail head.

"It's your basic assumption

I question." As she spoke, her ryes remained fixed on

him.

"Yes?" He swivelled

uncomfortably in his chair, opening himself to her attack.

"You assume that power

will be concentrated in a few key Centers, but what

if it is widely distributed throughout a government?"

"Even if power is dispersed,

communications will inevitably be focused in a few command

centers."

"Why inevitably?" She

spoke without hand gestures. Her body held its positions

as tenaciously as her mind.

"Because that is the

model that I've chosen to describe: a nation in which

communications are transmitted through closely held

channels." He strode over to point out the relevant

section on "Selection of models" in the manuscript she

was holding.

"Then isn’t it' tautological."

"Its political science.

We describe empirical situations. We have givens."

“But then its conditional,

not inevitable, right?”

"It's inevitable under

those hypothetical conditions," he shouted at her.

“Do you have a fever?”

she suddenly interrupted. “You’re soaking wet.”

She reached out towards

his shirt. Without thinking, he grabbed her wrists,

arresting them in mid air, clamping on invisible handcuffs.

He didn’t want her to feel the nervous sweat or know

what she aroused in him.

She pulled away with

a jolt and started moving back, towards the door.

He closed his eyes,

wondering if she would complain to the Dean. The last

thing he could afford was a scandal: HARVARD TEACHER

MOLESTS TUTEE was the headline he was envisioning as

the door banged shut.

But she was still in

the room. After locking the door, she was walking towards

him. Then, putting her arm on him for leverage, she

slipped into his lap. "I still say it's a tautological,

but so are you.”

That was it. Only two

months earlier Harvard summarily dismissed an Assistant

Professor of History for just such all indiscretion.

Yet, he knew that it was no use pretending that he could

be a rational calculator in this situation. He could

feel his excitement growing. He wanted Arabella more

than anything else. Up until now, it had been merely

a secret fantasy that he had managed to repress.

It took him only a

minute to unbutton her dress, and, with a firm tug,

pulled it over her head. Raising her hands in mock surrender,

she allowed him to finish undressing her.

She pressed her lips

to his lips with determination. Then her her right hand,

expertly guided by his own, began undoing his zipper.

Suddenly he heard footsteps

shuffling down the corridor. "You can't believe what's

happening in Washington," a distant voice was saying.

Foxx recognized it as the voice of Professor Edward

Wiley, the antitrust expert, who taught at the law school.

"Are you telling me that they are going to drop the

cartel case, Wiley?" said Professor W. L. Lock, Chairman

of the Government Department. Lock's office was next

to Foxx's.

Foxx froze as he listened

to Wiley and Lock chatting in the hall. They paused

for a moment, and then continued into Lock's office.

"They are now claiming

that national security transcends the criminal code

of justice," Wiley continued in an agitated voice.

"Bosh, it's crude oil,

that's all," Lock replied.

Foxx could hear Professor

Wiley in the next office explaining: ". . .The cartel

controls everything, ships, pipelines, refineries. If

the truth be known they control the British government.

The risks would be enormous...”

He could no longer

concentrate on what was being said in the adjoining

office. But Arabella seemed to enjoy their enforced

secrecy.

"Enormous, indeed,"

she echoed.

|